Last updated 11/1/2024 by KK

Overview

A token economy or late bank system allows instructors to provide deadline flexibility to students, eliminating the need for instructors to adjudicate excuses. This type of structure flexibility enhances student learning, reduces stress, and promotes equity.

What are tokens?

Tokens are a form of currency issued and controlled by the instructor. Students spend this currency during the course to buy exceptions to course rules (Nilson, 2014, 2016; Talbert, 2021).

Linda Nilson (2014) describes tokens in her book Specifications Grading: Restoring Rigor, Motivating Students, and Saving Faculty Time:

You allocate between one and five tokens to each of your students at the beginning of the course, and they are free to exchange one or more of them—it is your currency to control—for an opportunity to revise or drop an unsatisfactory piece of work to take a makeup exam or retake an exam, or to get a 24-hour extension on an assignment (p. 65).

Of course, since it’s 'your currency to control,’ you could adjust the number of tokens, length of extensions, and ways students can gain or use tokens.

While this type of token economy system is most associated with specifications grading, it can be implemented in a course with a traditional grading scheme. For example, it could replace your current policy for late and missed work. (Specifying such a policy in your syllabus is required by By-Laws, Rules and Regulations of the University Senate, II.E.2, Responsibility for Academic Assessment of Students.) In the context of a late policy, a token system is often called a “late bank,” but the concept is the same.

Benefits

Enhances student learning

Flexibility in grading and deadlines increases student participation, assignment quality, pass rates, and achievement (Hills & Peacock, 2022), but flexibility can create other issues.

Since the pandemic “students now seem to have 'this expectation of endless flexibility’” (Supiano, 2023, para. 19). Students can take advantage of instructors (Weimer, 2017) and instructors are left evaluating excuses, deciding where to draw the line and how to be fair. Responding to individual requests for assignment extensions, make-up exams, and extra credit can become a sizeable workload with large classes. “Many professors suspect the extensive flexibility students now expect might also be undermining their learning” (Supiano, 2023, para. 13). With too much flexibility, “students can get overwhelmed, mismanage their time, and lose the sense of continuity within a course” (Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, n.d., para. 3).

It’s important to strike a balance between ‘total flexibility’ and ‘toxic rigor’ to support learning (Supiano, 2023). Using tokens allows instructors to give students the level of flexibility that enhances student learning without it being a free-for-all. Instead of adjudicating requests, instructors can fairly provide flexibility within a constrained system.

In turn, students can manage for themselves when they want to spend a token, “empower[ing] them to make decisions about how to prioritize their academic work, balance deadlines, and manage their time” (Hills & Peacock, 2022, p. 14). Students report that having extra time when needed from this type of built-in extension system improves the quality of their assignment (Schroeder et al., 2019). Giving students control over their learning increases their accountability and facilitates self-regulated learning (Hills & Peacock, 2022).

Promotes equity in the classroom

Implementing a token system can also promote equity in the classroom. Proactively designing courses to accommodate learners with a wide variety of experiences and contexts fits within the framework of Universal Design for Learning (CAST, 2024; Hills & Peacock, 2022).

UDL is a framework to guide the design of learning environments that are accessible, inclusive, equitable, and challenging for every learner. Ultimately, the goal of UDL is to support learner agency, the capacity to actively participate in making choices in service of learning goals (CAST, 2024, para 1.).

A token system or late bank specifically addresses UDL Consideration 7.1 — optimize choice and autonomy — by providing choice related to the timing of task completion.

While a token system within the UDL framework benefits all learners, it supports many marginalized populations in particular, including: non-traditional students, students of color, women, first-generation students, low-income students, students with disabilities, neurodiverse students, LGBTQIA+ students, and undocumented or DACAmented students.

Nontraditional students

Nearly three-fourths of U.S. college students are nontraditional students. While definitions vary, nontraditional students generally include students that: enroll one or more years after graduating high school; have earned a GED certificate; are 25 years or older; have caretaking responsibilities for a child or adult; work full-time; are financially independent; or take classes on a part-time basis (Muniz, 2022). A major barrier in degree persistence for non-traditional students, who are disproportionately women, people of color, and first-generation students, is experiencing interrole conflict between their different roles as student, parent/caretaker, and employee (Markle, 2015; Rothwell, 2021). It's not hard to imagine most students—nontraditional or not—needing an exception at some point in the semester given their other roles outside of the classroom.

Students not privy to the “hidden curriculum”

The students that arguably are most in need of an exception are least likely to ask for one. Women request fewer deadline extensions than men despite feeling more time stress (Flaherty, 2021; Whillans et al., 2021). Asking for an exception to course rules is part of the 'hidden curriculum' of higher education, "the set of tacit rules in a formal educational context that insiders consider to be natural and universal" (Jaschik, 2021, What is the "hidden curriculum"? answer, para. 1). First generation college students, which are nearly a third of all first-year students (Seale, 2019), many of whom are also low-income and underrepresented minorities, often have to learn the 'hidden curriculum.' In contrast, "those with prior knowledge (students with similar educational backgrounds to the new educational context) believe [the tacit norms and rules] to be natural, universal and simply 'how it’s done'" (Jaschik, 2021, What is the "hidden curriculum"? answer, para. 2). Many students simply may not know that they can ask for an exception.

Students with disabilities

A deadline extension accommodation is common for various disabilities (Hills & Peacock, 2022). As of 2020, the Center for Students with Disabilities provides services for approximately 4,000 students with disabilities (Center for Students with Disabilities, 2020), which is about 12% of UConn students (University of Connecticut, 2020). However, not all disabilities are diagnosed, and not all students with diagnoses access accommodation. “In a national longitudinal study in the United States (n=3,190), Newman and Madaus found that only 35% of post-secondary students who received special education services in secondary school disclosed their disability to their college (2015), citing concerns about stigma and discrimination as their main reasons for not disclosing (2015)” (Hills & Peacock, 2022, p. 5). Students with multiple marginalized identities, such as students of color, are contending with multiple layers of stigma and discrimination, are often less likely to receive a diagnosis, and may be more hesitant to disclose or seek support (Chrysocchou, Syharat, & Motaref, 2023).

Neurodiverse students

Students with some specific types of disabilities, such as neurodiversity and mental health challenges, can particularly benefit from a token system. Neurodiversity encompasses “neurological variations in human populations that result in differences in brain structure and/or function [and] often include[s] variations in learning, mood, attention, socialization, and other mental functions” (Chrysocchou, Syharat, & Motaref, 2023 slide 2). These variations come with strengths and challenges, and a token system specifically supports neurodiverse students’ challenges. Challenges include focus, memory, motivation, and working efficiently, which often can be accommodated with exceptions such as deadline flexibility and the ability to redo coursework. As with any disability, multiple layers of identity and stigma create barriers to accessing services and accommodations. Specific to neurodiversity, women are often underdiagnosed (Chrysocchou, Syharat, & Motaref, 2023; Hills & Peacock, 2022) and there is a “larger overlap between neurodiversity and LGBTQIA+ identity” (Chrysocchou, Syharat, & Motaref, 2023, slide 10).

A token system allows instructors to accommodate students with disabilities, particularly neurodiverse students, needing course exceptions regardless of diagnosis and documentation.

Students requiring privacy, such as undocumented and DACAmented students

Lastly, some students may not want to disclose the reason they need an exception. Many populations already described may be reluctant to "out” themselves for fear of stigma and discrimination, whether it be caregiving responsibilities, poverty, or disability. Additionally, undocumented and DACAmented students may need an exception unique to their immigration status; these students may not want to disclose that information in a request for an exception for fear of notification to immigration authorities, deportation, and family separation (Connecticut Students for a Dream, 2022). While the Dean of Students can provide students with some privacy from disclosing to instructors, it still requires student disclosure, and not every need for flexibility is an "extenuating circumstance."

A token system can promote equity by making the hidden curriculum explicit and exceptions available to everyone (Orón Semper & Blasco, 2018). Students don't need to have prior knowledge, worry about potential repercussions, or weigh disclosing personal information. This type of flexibility is ideal for optimizing learning in that it allows everyone access to successfully progress in their learning (Hills & Peacock, 2022), not just those privileged enough to ask for an exception or not need one in the first place.

Promotes student mental health

In the wake of the growing student mental health crisis on college campuses, institutions are investing heavily in improving student wellness (Mowreader, 2024). While some students with mental illness and addiction can be served by the Center for Students with Disabilities, many students with mental health disabilities struggle with obtaining a diagnosis and accessing accommodations (Hills & Peacock, 2022).

Moreover, “students without pre-existing mental health needs can experience periods of reduced well-being” (Schroeder et al., 2019), and “mental health struggles that do not meet the criteria of a diagnosable disability can also impact student learning” (Hills & Peacock, 2022, p. 6).

Adhering to deadlines is a common challenge for students experiencing mental health issues. With these issues climbing at an alarming rate — 88% of students report feeling overwhelmed by all that they had to do at least once in the last 12 months — most ‘normal’ students likely need an exception at some point in the semester (Hills & Peacock, 2022).

When students have access to extensions through a late bank system, students overwhelmingly report that it reduced their stress. Even students that do not use an extension report that just knowing the extra days were available lowered their stress (Schroeder et al., 2019).

Incentivizes certain behaviors without grade inflation

You get the behavior you reward. Instructors can award tokens to incentivize certain behaviors, such as attending or participating in class. Extra credit is often used for this purpose, but it can have the side effect of increasing a student's final grade without commensurate achievement. Generally, extra credit makes up for points lost due to poor performance or missed/late work. Contrarily, token economy systems allow students more flexibility in earning points on the initial assignment; students still must do the work to meet the learning objectives, and their higher grade indicates such achievement.

Challenges

Can negate equity benefits if not implemented with care

While a token economy has the potential to promote equity in the classroom, some ways of implementing the system can negate those effects.

Earning Tokens

Consider the method of earning tokens. Do you give everyone the same number of tokens or do students earn tokens throughout the course? Giving everyone the same number of tokens takes away the ability to use tokens to incentivize certain behaviors. Only awarding tokens for attending class or turning in work early may disadvantage populations already marginalized in higher education and most in need of flexibility. You might balance this by giving all students enough starter tokens while also allowing students to earn tokens for behaviors you want to incentivize.

Leftover Tokens

What do you do with leftover tokens? Some instructors allow students to cash in unused tokens for extra credit, the ability to skip the final, or some other privilege (Nilson, 2014, 2016; Talbert, 2021). This can encourage hoarding (Talbert, 2021) and negates using tokens to enhance learning and increase student achievement of learning objectives. Since your already privileged students are less likely to need to use tokens and are better able to hoard/save them, this setup can maintain the systemic status quo. You might balance this by limiting how many tokens can be cashed in at the end of the course and being thoughtful about the reward. Consider treating tokens like coupons in that they have no cash value and expire.

Can be too novel for students

For whatever reason, some students are confused by the concept of tokens. It’s a novel approach to late and make-up work, and some students can’t wrap their heads around it. Anecdotally, the students who struggle with the token economy system the most seem to be students who already routinely ask for extensions. They are already knowledgeable about the ‘hidden curriculum’ and have used this system to their advantage. The token economy system violates this construct and confuses them. A few even become angry at this perceived loss of privilege.

Related to the novelty, students also forget that tokens or the late bank exists. It's recommended to do a thorough explanation and walk-through at the beginning of the course with a few more reminders throughout. (Talbert, 2021). If you send out regular announcements reminding students of upcoming deadlines, which is best practice (Morrow et al., 2022), consider adding a reminder about using tokens on extensions.

Another thing to track

Perhaps your most burning question is "how do you keep track?"

How do you currently track exceptions? Yes, tokens are another thing to track, but ideally, the more systematic approach of a token economy is easier to manage and less mentally taxing than adjudicating excuses for extensions and make-up work (Nilson, 2016; Talbert, 2021). The next section will provide guidance on managing tokens.

Managing Tokens

There are a few ways to track tokens in HuskyCT/Blackboard, and the best method will likely depend on the size of your class, the number of tokens awarded, and overall flexibility in token usage.

Method 1: Assessment Tools

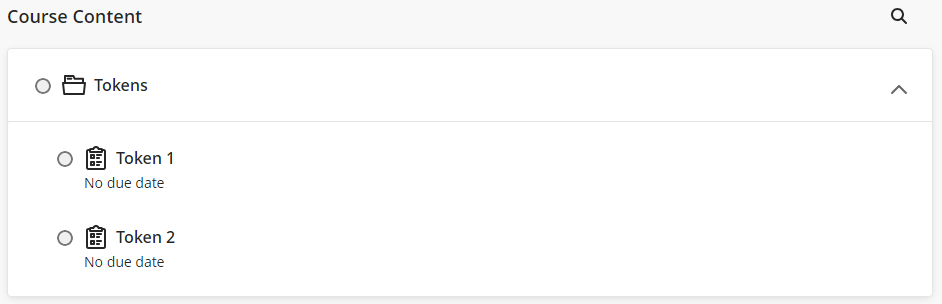

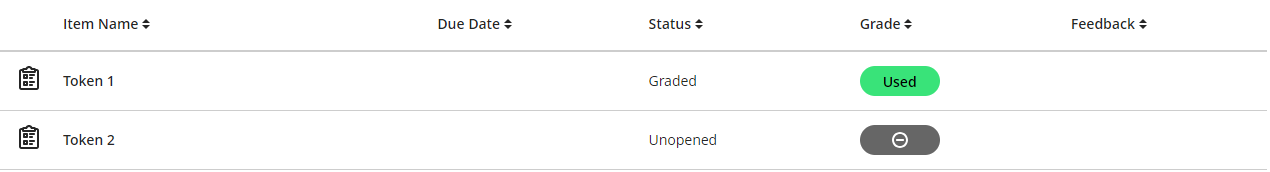

To track tokens with assessment tools, create a form or create an assignment for each token: Token 1, Token 2, etc.

When students want to use a token, they submit the assessment with a note about what they are using the token for. The instructor “grades” the assessment to mark the token as used (Kleinman & Schlesselman, 2021). Instructors can even set up a custom grading schema where 100% equals “Used.”

Using the assignments tool works well with classes with a limited number of tokens and no opportunities to earn more.

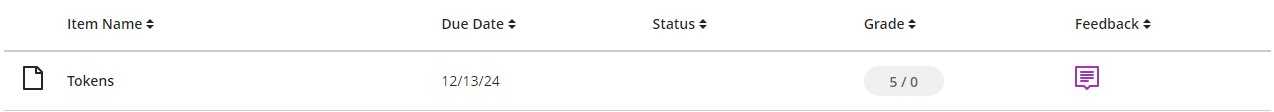

Method 2: Manual Grade Column

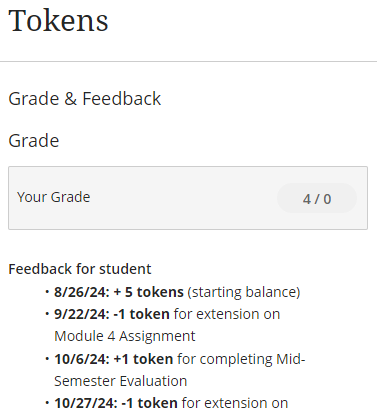

Another option is to track tokens as a running balance in one manual grade column. At the beginning of the semester, enter the starting balance for each student.

Provide students instruction as to how to redeem tokens, whether that be a Microsoft Form, email, or Messages within HuskyCT. As students earn or use tokens, update their balance (Talbert, 2021). You can also use the Feedback tool as a receipt, noting the date and reason each token was used or earned.

Using a manual grade column works well with classes that have opportunities to earn more tokens and more flexibility in their usage (e.g., allowing double extensions).

Additional Resources

Related Posts

- Specifications Grading: A Method to Improve Student Performance (UConn Knowledge Base)

- Inclusive Online Course Design & Facilitation (UConn Knowledge Base)

References

- CAST. (2024). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 3.0.

- Center for Students with Disabilities (CSD). (2020). History. University of Connecticut.

- Chrysocchou, M., Syharat, C., & Motaref, S. (2023, May 16). Inclusive teaching practices for neurodiverse students [Workshop]. CETL Day of Workshops, Storrs, CT.

- Connecticut Students for a Dream. (2022, February 24). No papers, no fear: Educator accomplice training [Workshop]. Virtual.

- Flaherty, C. (2021, November 2). Study: Women request fewer deadline extensions than men. Inside Higher Ed.

- Hills, M., & Peacock, K. (2022). Replacing power with flexible structure: Implementing flexible deadlines to improve student learning experiences. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 10, 1–25.

- Jaschik, S. (2021, January 19). 'The Hidden Curriculum'. Inside Higher Ed.

- Kleinman, J., & Schlesselman, L. (2021, August 19). Specification grading: An alternate means of assessing learning based on mastery and process [Workshop]. Virtual.

- Markle, G. (2015). Factors influencing persistence among nontraditional university students. Adult Education Quarterly, 65(3), 267-285.

- Morrow, D., Keefe, K., & Wang, S. (2022, May 6). Managing your online course. eCampus Knowledge Base.

- Mowreader, A. (2024, August 19). Survey: Getting a grip on the student mental health crisis. Inside Higher Ed.

- Muniz, H. (2022, January 26). What is a nontraditional student?. BestColleges.

- Nilson, L. (2014). Specifications grading: Restoring rigor, motivating students, and saving faculty time. Stylus Publishing.

- Nilson, L. (2016, January 19). Yes, Virginia, there's a better way to grade. Inside Higher Ed.

- Orón Semper, J. V. & Blasco, M. (2018). Revealing the hidden curriculum in higher education. Studies in Philosophy & Education, 37, 481–498.

- Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Flexible structures in course design. Yale University.

- Rothwell, J. (2021, January 29). College student caregivers more likely to stop classes. Gallup Blog.

- Seale, S. (2019, November 1). Not your traditional student: Changing demographics on campus. Association for Nontraditional Students in Higher Education (ANTSHE).

- Schroeder, M., Makarenko, E., and Warren, K. (2019). Introducing a late bank in online graduate courses: The response of students. Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(2), 7.

- Supiano, B. (2023, February 13). Students demand endless flexibility — But is it what they need?. Chronicle of Higher Education, 69(12), 1–7.

- Talbert, R. (2021, November 8). The care and feeding of tokens. Grading for Growth.

- University of Connecticut. (2020). Fact Sheet 2020.

- Weimer, M. (2017, November 3). 'Prof, I need an extension …'. Faculty Focus.

- Whillans, A. V., Yoon, J., Turek, A., & Donnelly, G. E. (2021). Extension request avoidance predicts greater time stress among women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(45), e2105622118.